Teaching to the Test

What could be a more fascinating blog entry than a long screed against multiple-choice tests? Sex manuals? An interactive drum machine? A masonic conspiracy involving the Mona Lisa? If you don't care about librarians, multiple-choice testing, or assessment, you should probably skip this posting and look down the page to some other recent entries on juicier, less-arcane topics.

Well, you had your chance.

This week's New York Times story about widespread SAT misreporting is yet another reminder of the hazards of basing either college admission or first-year placement on fallable standardized tests. Yet, on February 14th, I received a surprising valentine from the Educational Testing Service about their new Information Literacy examination. In the past, I've expressed concerns about how ETS may be introducing another distorting multiple-choice test that emphasizes tool literacy over rhetorical awareness and sensitivity to social and disciplinary context. There's been no love lost between us, but ETS made its appeal in good faith, so I figured it was only right to evaluate the actual demo with an open mind.

This was the ETS e-mail pitch:

Measure your student's ability to find and communicate information effectively.

USE THE NEW ICT LITERACY ASSESSMENT FROM ETS

The ability to obtain information, analyze it and communicate it quickly and effectively can mean the difference between success and failure in college and in the workplace.

That's why ETS developed the ICT Literacy Assessment.

The assessment's real-time, scenario-based tasks assess the critical information and communications technology (ICT) skills that are required of today's college and technical school students.

Score results may be used to assess individual student proficiency, plan curricula to address ICT literacy gaps, inform resource-allocation decisions and provide evidence for accreditation. This secure test measures student information and communication technology literacy proficiency at two levels of difficulty: Core and Advanced.

The Core Level Assessment, appropriate for all community college students, students in their first and second years of college, and high school seniors, helps administrators and faculty measure the cognitive proficiencies of students doing entry-level course work. It also enables academic advisors to make informed decisions on students' readiness for college.

Unfortunately, their online demo requires revealing an onerous amount of personal information to gain access. So imagine my further irritation when I discovered that the implied information design curricula still seems only to emphasize what the American Library Association has called "Tool Literacy." Although the interfaces shown represent unbranded graphics in order to display generic document illustrations, it stresses negotiating menus rather than the acquisition of more complex and critical visual literacy skills.

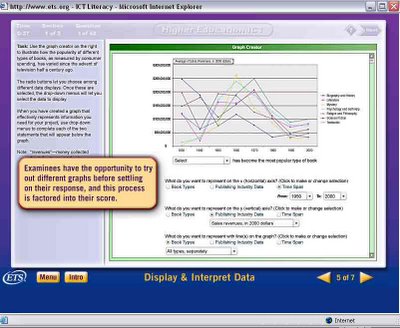

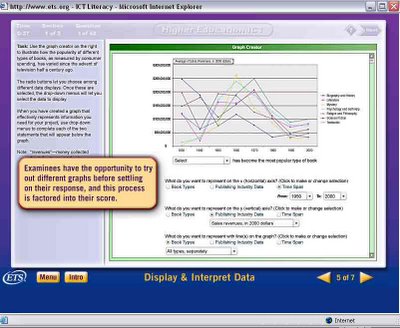

For example, the sample graph problem about consumer spending on different categories of books since 1930 would surely get a low grade from information design expert Edward Tufte. On the "successful" graphic, lines are only differentiated by color, and many of the gradations between individual hues don't read at a distance. Furthermore, the "key" to the "good" graph is arbitrarily organized and hard to read.

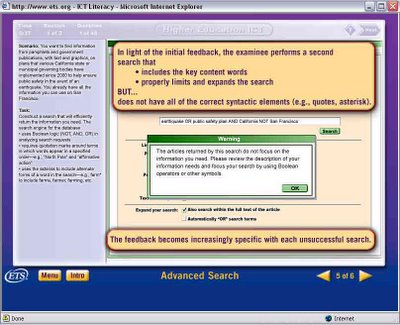

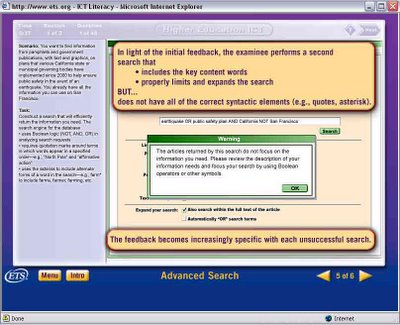

In the second part of the demo, the test subject is clearly situated in the context of higher education. Yet as a hypothetical college student, he or she is implicitly discouraged from drawing on the campus's disciplinary knowledge bases or its human assets. This "advanced search" scenario involves going to a university library to get information from government publications about earthquake safety procedures in California. Although it does introduce students to the concept of Boolean operators, it doesn't offer more important library tips about using subject guides or approaching reference librarians with appropriate questions.

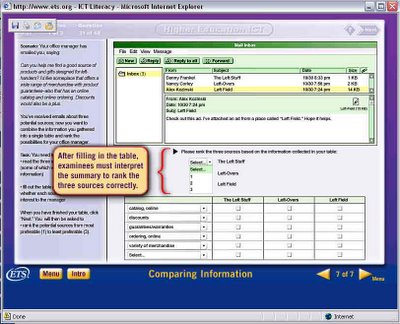

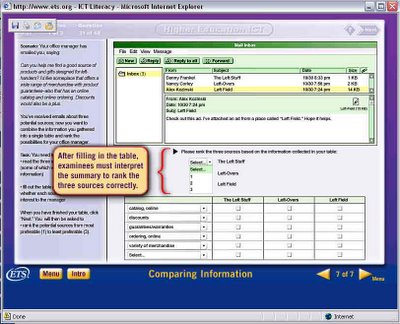

Finally, in the "real world" post-graduation part three, the test-taker assumes the identity of a drone in a large architectural firm faced with analyzing three separate project e-mails and also evaluating three recommended webpages from the senders. But it is difficult to analyze e-mail with nothing about information sharing, coping with hierarchies, or the Realpolitik of organizational dynamics to go on. Furthermore, the examples may overestimate the information literacy skills of students who often fall for hoax web pages or sites with stealth marketing agendas. As I am arguing in Virtualpolitik, e-mail miscommunication has contributed to many public policy disasters and scandals, and even "authoritative" government websites often demonstrate how conflicting stakeholders can generate mixed messages, or ones that are compromised by corporate interests.

From my information literacy perspective, I would say that Project SAILS is developing a much better multiple-choice tool, which is actually being facilitated by university librarians. Yet I don't think any such limited format could ever adequately model the complexities of real searches and forays into electronic communication. There are too many correct paths to an information literacy goal and too many wrong paths as well.

From my information literacy perspective, I would say that Project SAILS is developing a much better multiple-choice tool, which is actually being facilitated by university librarians. Yet I don't think any such limited format could ever adequately model the complexities of real searches and forays into electronic communication. There are too many correct paths to an information literacy goal and too many wrong paths as well.

Well, you had your chance.

This week's New York Times story about widespread SAT misreporting is yet another reminder of the hazards of basing either college admission or first-year placement on fallable standardized tests. Yet, on February 14th, I received a surprising valentine from the Educational Testing Service about their new Information Literacy examination. In the past, I've expressed concerns about how ETS may be introducing another distorting multiple-choice test that emphasizes tool literacy over rhetorical awareness and sensitivity to social and disciplinary context. There's been no love lost between us, but ETS made its appeal in good faith, so I figured it was only right to evaluate the actual demo with an open mind.

This was the ETS e-mail pitch:

Measure your student's ability to find and communicate information effectively.

USE THE NEW ICT LITERACY ASSESSMENT FROM ETS

The ability to obtain information, analyze it and communicate it quickly and effectively can mean the difference between success and failure in college and in the workplace.

That's why ETS developed the ICT Literacy Assessment.

The assessment's real-time, scenario-based tasks assess the critical information and communications technology (ICT) skills that are required of today's college and technical school students.

Score results may be used to assess individual student proficiency, plan curricula to address ICT literacy gaps, inform resource-allocation decisions and provide evidence for accreditation. This secure test measures student information and communication technology literacy proficiency at two levels of difficulty: Core and Advanced.

The Core Level Assessment, appropriate for all community college students, students in their first and second years of college, and high school seniors, helps administrators and faculty measure the cognitive proficiencies of students doing entry-level course work. It also enables academic advisors to make informed decisions on students' readiness for college.

Unfortunately, their online demo requires revealing an onerous amount of personal information to gain access. So imagine my further irritation when I discovered that the implied information design curricula still seems only to emphasize what the American Library Association has called "Tool Literacy." Although the interfaces shown represent unbranded graphics in order to display generic document illustrations, it stresses negotiating menus rather than the acquisition of more complex and critical visual literacy skills.

For example, the sample graph problem about consumer spending on different categories of books since 1930 would surely get a low grade from information design expert Edward Tufte. On the "successful" graphic, lines are only differentiated by color, and many of the gradations between individual hues don't read at a distance. Furthermore, the "key" to the "good" graph is arbitrarily organized and hard to read.

In the second part of the demo, the test subject is clearly situated in the context of higher education. Yet as a hypothetical college student, he or she is implicitly discouraged from drawing on the campus's disciplinary knowledge bases or its human assets. This "advanced search" scenario involves going to a university library to get information from government publications about earthquake safety procedures in California. Although it does introduce students to the concept of Boolean operators, it doesn't offer more important library tips about using subject guides or approaching reference librarians with appropriate questions.

Finally, in the "real world" post-graduation part three, the test-taker assumes the identity of a drone in a large architectural firm faced with analyzing three separate project e-mails and also evaluating three recommended webpages from the senders. But it is difficult to analyze e-mail with nothing about information sharing, coping with hierarchies, or the Realpolitik of organizational dynamics to go on. Furthermore, the examples may overestimate the information literacy skills of students who often fall for hoax web pages or sites with stealth marketing agendas. As I am arguing in Virtualpolitik, e-mail miscommunication has contributed to many public policy disasters and scandals, and even "authoritative" government websites often demonstrate how conflicting stakeholders can generate mixed messages, or ones that are compromised by corporate interests.

From my information literacy perspective, I would say that Project SAILS is developing a much better multiple-choice tool, which is actually being facilitated by university librarians. Yet I don't think any such limited format could ever adequately model the complexities of real searches and forays into electronic communication. There are too many correct paths to an information literacy goal and too many wrong paths as well.

From my information literacy perspective, I would say that Project SAILS is developing a much better multiple-choice tool, which is actually being facilitated by university librarians. Yet I don't think any such limited format could ever adequately model the complexities of real searches and forays into electronic communication. There are too many correct paths to an information literacy goal and too many wrong paths as well.Labels: hoaxes, information literacy, teaching

1 Comments:

At my university, we have something called "discovery tasks," designed to teach freshmen in our humanities breadth course how to navigate library resources AND get a taste of information literacy of the sort that Liz describes. The kids hate it, for the most part, and so do the instructors (it's on top of a heavy reading and writing load), but I can see the point of such exercises better after reading about this version of it.

Post a Comment

<< Home