The Bottom of the Pyramid

This week the Institute for Money, Technology & Financial Inclusion hosted a conference about the "Bottom of the Pyramid" that frequently explored and critiqued the thesis of CK Prahalad in The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits, which argues that aiming corporatized products at those living at the very bottom of the social ladder will enable markets to alleviate poverty while giving do-gooders a respectable profit by aiming for a kind of long tail that aggregates small sums and micropayments and often uses mobile phones and other kinds of ubiquitous computing technologies to foster exchange.

This week the Institute for Money, Technology & Financial Inclusion hosted a conference about the "Bottom of the Pyramid" that frequently explored and critiqued the thesis of CK Prahalad in The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits, which argues that aiming corporatized products at those living at the very bottom of the social ladder will enable markets to alleviate poverty while giving do-gooders a respectable profit by aiming for a kind of long tail that aggregates small sums and micropayments and often uses mobile phones and other kinds of ubiquitous computing technologies to foster exchange.Microsoft India researcher Aiswarya Ratan argued that instead of having "top of the pyramid producers focusing on bottom of the pyramid consumers," she was a champion of "the opposite" formulation in which "bottom of the pyramid producers serve top of the pyramid consumers" in order to facilitate the access to markets that many feel is an important component of a social justice agenda. As she pointed out, the most naive do-gooder approach ignores an important question: "Why should the poor care about the rich?" Ratan pointed to companies like Masuta Silk Producers, SEWA Trade Facilitation, the Gujurat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation, and Calypso Foods that often serve luxury markets and urban environments by appealing to the aspirations of the rich. Ratan argued that in these situations "technology works as an amplifier of whatever you are doing" to enabling exchange with the poor. However, if mere "disintermediation" is the central aim, programs only have about a 6% impact on the income of a poor rural farmer. In contrast, programs devoted to information dissemination like Digital Green that use simple video technology with "no PCs, no phones" create bigger 30% to 40% gains by using recognized practices around social networks, videorecording, and collective television watching and products with markets like organic Tasar silk yarn. Like many at the conference, Ratan asserted that "government as single most destructive force” in cooperatives. She closed with the example of Mumbai’s dabbawallas who transport 200,000 tiffin boxes to office workers at lunchtime and how calls on mobile phones can be used for either production and consumption.

Anthropology professor Hsain Ilahiane claimed in "Moving Beyond the Base: Mobile Phones and the Expansion of Mobile Phones in Morocco" that it was important to understand how mobile phones express "human agency" in a country that is 125th on the Human Development Index but in which 1 in 3 citizens have a mobile phone. Rather than emphasize "ICT gadgets," Ilahiane showed a slide of a man kissing his everyday mobile phone. His talk emphasized how Hrayfiya or skilled workers were "professors of bricolage" who achieved a 61% increase of income from mobile phones, which added up to a 105% increase when informal social economic benefits and the effects of bricolage were included. He also argued that the device was "Made for Maids" who could take advantage of the "perpetual contact" and "circle of opportunity" that such devices offer, particularly in an economics often dominated by the role of moonlighting. As on of his informants, a Berber plumber asserted, the mobile phone is "the sixth pillar of Islam." Like Ratan, he questioned the model of "selling to poor" and extracting more of their wealth. He also agreed that these societies need the privatization of ICT sector to get rid of baksheesh system, but he said "cou cannot arm them with a mobile phone" and that it was "not a magic bullet."

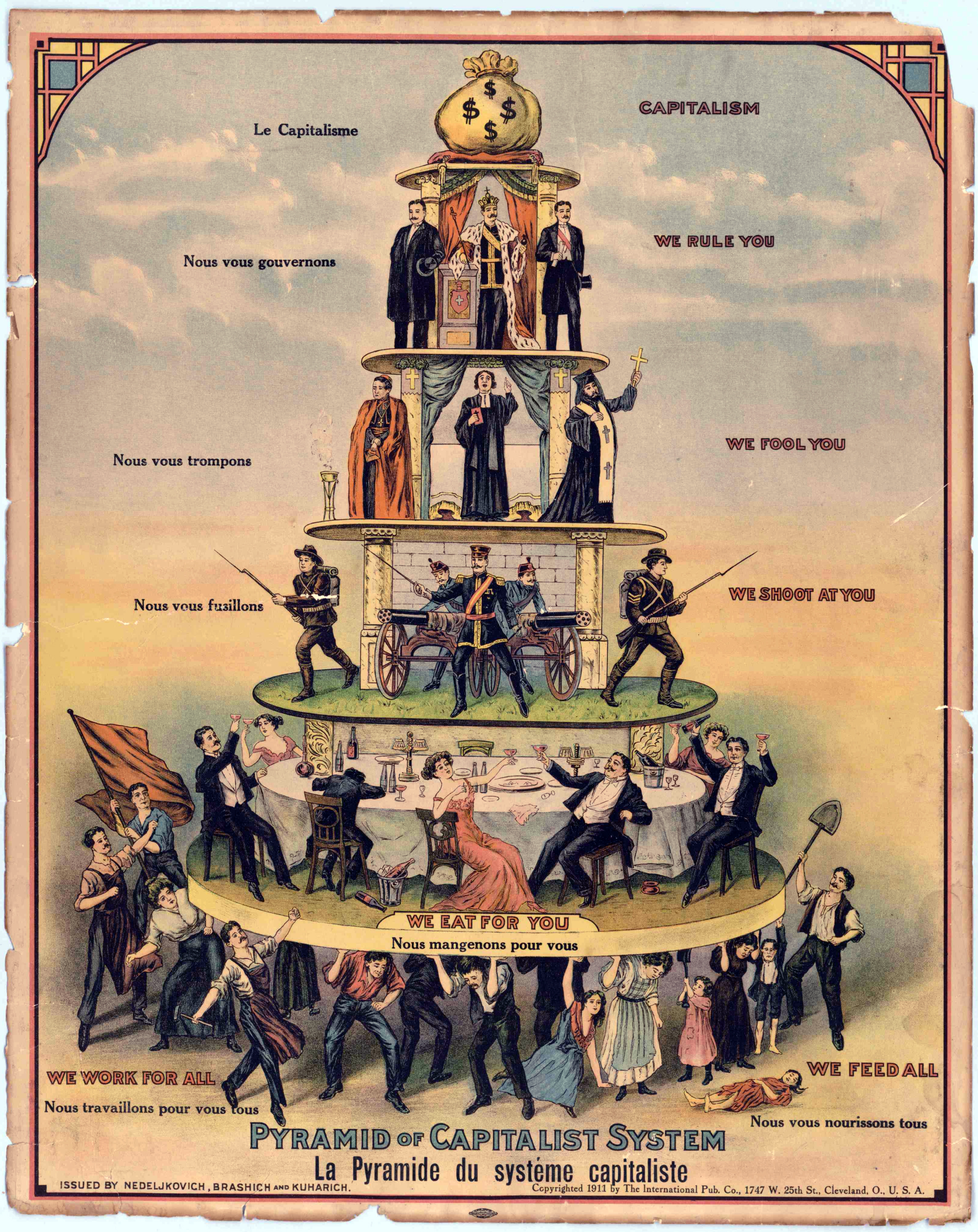

During the response period, Scott Mainwaring presented some ways to think about the "figure of the consumer or the fiction of the consumer" and the "image of the entrepreneur and what is it privileging." How, he asked, does the rhetoric of "the worker and worker’s rights" play in BoP models?

In thinking about financial services for the poor, Julia Elyachar insisted on the need for a "more nuanced approach" based on her fieldwork among women in Cairo. In thinking about the payment space, she argued that it was important to consider how what Malinowski called "phatic communion" and what Roman Jakobson considered to be the phatic channel for communication functions in financial transactions, even those that include the interventions of multinational corporations, international NGOs, or technological delivery systems. In other words, there is more to study, according to Elyachar, than production or consumption.

One of the most interesting papers at the conference was from Olga Morawczynski who writes about the adoption of the mobile payment system M-PESA in Kenya, which has been a remarkably fast growing application with a user base of nearly 7 million people in a country of 39 million people . This particular application has actually grown even faster than the mobile phone, since the Safari.com carrier only has 8 million customers. Subscribers to M-PESA an make deposits and withdrawals and the system has allowed person-to-person transfers as well, which is important for migrant laborers in cities who send money home to families in rural areas. Morawcynski reminded the audience about the research of Lauriston Sharp, who talked about the unintended consequences of inventions like the steel axe, to introduce her thesis that M-PESA doesn't necessarily create the utopian forms of social choice, economic freedom, and personal mobility that many Western neoliberal advocates promote by using it as an example. Her fieldwork in Kibera and Bukura showed that there were costs created by switching from the old systems that relied on bus companies and post offices, based on detailed financial diaries kept by 8 workers from Kibera, where citizens are prohibited from owning land, who were mostly male, and 6 dependents from Bukura and surrounding rural villages, who were all female. She discovered that participants were using M-PESA as a method of savings that was part of a variety of informal methods that constituted what she called a "portfolio" approach. She discovered that these migrants who were mostly unemployed or informally employed transferred on average five transfers per month to spouses, siblings, children, parents, in-laws, and friends (in decreasing order of frequency). Women also used the cell phone technology to receive money from siblings and children, sometimes in opposition to their children.

In Dreams from My Father U.S. President Barack Obama describes his own disappointment at discovering how the relatives in Africa that he was so looking forward to becoming acquainted with were quick to begin asking him for money shortly after his arrival. He acknowledges that some of his encounters with new-found siblings were strained by demands for money that were considered within the cultural norm. Imagine how much more intense these interactions would be, if he could be tethered to them via his mobile phone?

Morawcynski detailed how transferring money in bits had a positive effect when measured as an increase in total income inflows to rural households from 5 to 30%. But this increased funding also correlated with increased requests, so that the "phone were used to constantly call husbands." This tactic of requesting small money allowed the women to diversify their income sources as well. Family members became very protective of their phones, which would be hidden sometimes from spouses. The acquisition of a phone by rural women allowed them to also exploit other contacts. As women had more financial autonomy, it led to increased tensions between husband and wife. It also encouraged increased tensions between rural residents who began to surveil each other to discover who was receiving M-PESA transfers by monitoring the coming and going of others. Parties were thus subject to additional requests for money within own communities. Finally, home visits by urban workers decreased, given the easy transfer protocols, so they stayed closer to their mistresses in the city.

Bill Maurer gave a broader talk about "the emerging payment space" and its discourses, practices, regulations. He argued that the financial community and the academy were paying attention to Nobel Prize winner Yunus and the Grameen Bank, the worldwide spread and adoption of mobile phones, and the renewed drive for fee-based revenue or average revenue per user (ARPU). But he argued that a number of larger social questions were being ignored in tracking high-profile personalities, initiatives, programs, and corporate brands. For example, "Are we participating in an enclosure of that commons?" and "Who is in the payment space?" are being inadequately interrogated, according to Maurer. He offered three basic models: 1) Take what is already there and scale it up, such as when airtime minutes become a form of currency, 2) Create something new but based on what is already there, such as M-PESA, and 3) Layer new functionality, such as is the case with new Point of Sale terminals. However, he argued that the aim for total interoperability and market dominance could rarely be satisfied by these projects, particularly when market players all dreamed of "trying to be the Western Union in the payment space." Such "leveraging" of "poor people’s networks and access" "complicates and transforms the BOP perspective," but he argues that there are some unscripted potentials that are realized at the level of lived practices, which include phenomena in the following categories:

1) Mashups, hacks, and the using of unintended affordances, which could be thought about from design perspectives

2) New channels for money and finance, and new forms of money that could be additive, not supplantive, particularly in a complex monetary ecology lacking global interoperability. (At this point he reminded the audience, "look in your own wallet" and try to move currency around.)

3) Regulation in/of the payment space. Here he pointed out "unrealized effects and unintended consequences" such as identity management, Know Your Consumer compliance, and Anti-Money Laundering /Combating the Financing of Terrorism

4) Technological utopianism in the privileged social milieu of universities and corporations that in the 80s and 90s created flexible workforces of their own and faced the instability of the dot.com bubble bursting and current crisis. In other words, Maurer thinks it is important to include "the story of 'us'" and the social history that has yet to be told

5) Mobile moneys as new experiments with money; tinkering with money’s classic functions; this complicates the critique (of extraction, dispossession, etc.).

As Maurer said, money itself is up for discussion here for the first time since debates about gold and silver standards.

He also drew what could be a controversial analogy between the extraction and exploitation of the bottom of the pyramid and the ways that even slavery tolerated and even encouraged subsistence growing and zones of economic autonomy. (To test Maurer's hypothesis, see the work of Virtualpolitik pal geographer Judith Carney for more about the complicated agricultures, economies, and knowledge networks of African slaves in the New World.) In "everyday informal experiments" related to what "looks like extraction from the bottom of the pyramid," Maurer argues there are sites of productive testing grounds in places like the British Virgin Islands where two competing cell phone carriers now sponsor the annual Emancipation parade.

He also pointed out that "microfinance is happening in your back yard" with projects like Microfinance California and Bank on California, since the "unbank" is part of the developed world as well. For Maurer the key questions involve the unit of exchange, which can be "just talk," particularly when interventions require a "critical mass of trust" and are "communications-based."

To sum up what she called the most "disciplinary panel" at the conference, since it featured three anthropologists, Isha Ray used Pierre Bordieu's definitions of social capital, cultural capital, and economic capital to understand how their interchangeability might function as a store of value, a medium of exchange, and numerator that is "all about relationships not just financial transactions."

As if answering Maurer's call for more of the social history of this particular form of corporate culture aimed at the developing world, which combines rhetorics of philanthropy with systems of extraction, Anke Schwittay of the RiOS Institute in "Taking Prahalad High-Tech" argued that it was useful to look back at the model of "global corporate citizenship" that was launched by Hewlett Packard as part of a series of experiments in "e-inclusion." She also argued that in the cast of the HP e-inclusion initiative in Andhra Pradesh and its involvement in public contracts this history couldn't be divorced from regional politics involving The Chief Electoral Officer of Andhra Pradesh, the Telugudesam Party, and the political career of Chandrababu Naidu. She also claimed that HP’s work had some secondary consequences that promoted civil society, such as helping develop a system of ID cards or a method for filing complaints online against the government, although the effectiveness of such protocols could certainly be subject for debate. She also discussed the company's involvement in the "Digital Progress" initiative in which low-income people in the developing world went door-t0-door with PDAs to sell e-services. Sometimes these projects featured moving women into this door-t0-door workforce and the testing of new products and services, such as those for digital photography, to the BOP market. Faced with different timelines and initiatives that were all relatively short-term, these initiatives did not outlast the CEO who launched them.

As discussant, Paul Dourish observed that the issues raised in the conference was also helpful for his thinking about a current project in Australia that involved teaching cultural lore from indigenous peoples. He described himself as interested in "social and cultural infrastructures" and influenced by the work of Geoffrey Bowker on the ethnography of infrastructure that involve questions of access and the role of social practices.

In "The Hidden Phantasm of Corporate Social Structure: The Fight That Surprises Everyone, Even You" Tony Salvador from one of the sponsor groups, the Intel Corporation, came out swinging and announced himself as the representative of a "large multinational corporation" that makes microprocessors with an investment cost of four billion dollars per factory to propagate a highly optimized system with heavily policed cultural boundaries. As an observer of the proceedings, he felt compelled to point out to the audience of academics that CK Prahalad is "one of us not one of you," affiliated with the University of Michigan as the corporate guru who got rich by developing the concept of "core competency" and counts on continuing to make money on consulting fees. His book actually offers another "vehicle for him to consult" by appealing to the "collective imaginations of the multinationals." Like the presenter of the first paper, Salvador was not persuaded by the appeal of "nontraditional customers," because "consumption isn’t going to alleviate poverty."

As Salvador put it baldly, "I don’t see anything here to invest in." He expressed his irritation at "trying to understand cooperative models" and noted the hit or miss nature of many initiatives. For example, he asked why cybercafés work in China and not in India and why information kiosks were worth investing it if they were only better in relationship to other startups in India. As he stated it flatly, such projects were generally "not palatable to the multinationals."

What was important, he suggested, was the graphic on his single slide, the notion of exchange, which he represented with the letter "X" and a triangle to symbolize the delta of change. As he said, "people are very suspicious of handouts," and the experiences of the iVillages for HP only confirmed that. Things that can be characterized by Latour’s black box present a challenge to companies that are also highly optimized socially, where stakeholders are seeking "a good deal relative to what they've got." Appeals for "computers for kids to go to school so they can have access to these resources" don't make sense to respond to, particularly when, as Kentaro Toyama has said, others see multinationals only as a "big bag of cash," and until recently corporations could be confident that they could invest their capital in the market and do much better. A desire to change systems and "unpack black boxes" can produce "a whole lot of difficulty."

Nonetheless, Salvador pointed out that -- at least in Intel's case -- this engagement with the needs of the developing world was fixed in the company's mission statement, since the corporation wants to we wants to grow the market and have a positive impact on local sustainable development.

Given the scholarship now being done on the history and rhetoric of the One Child Per Laptop project from MIT, it is surprising that Salvador didn't say more about his own role in developing workable design for the low-cost Classmate PC, as the video above shows. Although he did mention the challenges of a "new product" and "new geography" and the "business risk and social risk" involved, it would have been interesting to here more about the current status of the initiative and the challenges it has faced. Perhaps I should "Ask Tony."

Salvador was followed by Heather Horst, who is known for her work with Daniel Miller about the cell phone in Jamaica. Horst described the appeals of different advertising campaigns in teh mobile communication landscape and how the Cable & Wireless carrier made a mistake by overemphasizing business and colonial user identities before going with "a fresh approach" to compete with rivals Digicel and miPhone. Unfortunately, as Horst noted, all this investment in youth technology shows a fundamental lack of attention to the elderly poor, which plagues many BoP corporate programs.

Renee Kuriyan of Intel's People & Practices Group opened by citing James Ferguson and the notion of the anti-politics machine and William Mazzarella’s research on how the consumer serves as an invented category. With the "broadband infrastructure rollout," Kuriyan argues that technocrats are promoting technology consumers as apolitical and neutral. However, she pointed that not only are there governments who actively subsidize rather than just regulate, as in the case of Portugal building PCs in the name of nation-building or state agencies that outsource traditional government services, these initiatives that also allow the poor to identify themselves with the middle class shapes public understanding of political agency. Kuriyan also noted that the M-PESA advertisement, which I have reposted above, features a giant ledger and the mechanisms of tradiitonal bureaucracy.

Vijay Gurbaxani of CRITO emphasized his own ethos as a former Indian national who knew about community-based technologies and the bottom of the pyramid from personal experience growing up in Mumbai . As he said, "You cannot avoid the bottom of the pyramid" there. He talked about being a boy watching a child buying single slice of mango because that was all he could afford and not sharing his chocolate shipped to him from a father working abroad because you "do not want to create a demand" that can't be satisfied. After waxing rhapsodic about how "Walmart has done more for people" in distress than other corporations by having superior logistics for crises like Hurricane Katrina and a business model that aims products at the blue-light special consumer, he described how the label "made by USA" actually signified the products of the Ulhasnagar Sindhi Association, the refugee camp in which his mother lived. He also narrated the economic dramas of the family's hired help in "Leela’s Story" that described a household maid with an abusive husband for whome Gurbaxani's mother was a banker, and "Amrit's Curse" in which the family driver was steeped in debt because of the financial decisions of his uncle. Not only were money transfers common in his more privileged family, where currency was coming from Kuwait and Bahrain, but also he was familiar with local practices involving Hundis and Hawalas, which were based on trust and had no records and thus also later became tools for terrrorism. As he asserted, the "middle of the pyramid is only starting to see changes" now with the availability of mortgages, and it was apparent to him how challenging bureaucracies that slow down the rich and middle class could be to the poort, as he told how his visit to the government-owned Bank of India, where he had gone to handle a transaction for his mother, and where the crowd lined up had to serve as an advocate for an illiterate plumber who couldn't authenticate himself except with a thumbprint when faced with cashing a check for 700 rupees from a customer.

Gurbaxani also explained his experiences with studying FINO and their attempts to serve the "500 to 600 million people who don’t bank" by partnering with banks and insurance companies. He explained that contrary to Western expectations the poor prove to be "net savers." He also described how bank procedures may include provisions that forbid clients to be married to alcoholics or require two fingerprints, given the likelihood of the poor to lose fingers from occupational hazards. Authenticating people in India is particularly challenging, he noted, because the only national identity card is a ration card that doesn't serve the whole nation, since there is not the equivalent of a Social Security Number in India.

Speaking as another multinational corporate agitator, Paul Thomas, chief economist at Intel, took issue with some of the basic propositions of CK Prahalad's work and the emphasis of the conference itself. First, he disputed the number of people with a per capita income of less than $2 a day, which he characterized as describing 2 billion rather than 4 billion people. Like an earlier conference he attended about the "Emerging Middle Class," Thomas argued that the very title contained some troubling assumptions. Second, he said PPP should not be used, since purchasing power parity means little when the costs of living are more expensive in the developing world that here. As an example of this "poverty tax" he cited the "cost to get a clean glass of water in Manila." Third, he insisted that "market exchange rates matter" and the BoP was "not a compelling market," since it only accounted for 1 to 2 trillion dollars out of 50 trillion dollar world economy. Furthermore, the desparately poor are only one disease, injury, monsoon, crime, war, misunderstanding away from disaster, in addition to facing social and legal barriers to progress. Thus, poor people can be even poorer, and he cautioned, "let’s not exaggerate their command of resources" or fall under the spell of the "romance about the bottom of the pyramid."

Yet, he said, speaking for his own multinational corporation, "You don’t want to be hated." BoP initiatives could be important for "brand management," particularly now that the Internet can spread bad PR from an single individual's experience all over the world. He pointed out how Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Toyota, Honda, Avon, and Johnson & Johnson know that promoting good corporate citizenship is "like saying 'don’t forget to breathe.'" He described himself as "tired of hearing" about Monsanto's failure and Unilever's success in this venue. He also said that "appropriate technology is overdiagnosed," athough "delivery and payment probably do need to be customized." Besides, he reminded his audience, "digital products are always used in surprising ways." To demonstrate this point he recalled an anecdote in Tedlow’s biography of Andy Grove that described how Intel's "culture of planning" missed the fact that MPUs would be mostly CPUs, because "personal computers were not on the list" even though such computers already existed. He closed by pointing out that "every market is potentially disruptive," and "we are all one terrible calamity away from disaster." Given his willingness to make gloomy but realistic predictions about the U.S. economy to the public, Thomas's words rang particularly true.

Among those in the audience I enjoyed meeting UCI business student Kristen Parrinello , a veteran of the American Himalayan Foundation and the 10 Percent Solution, through her Twitter Invisible Work feed.

Labels: conferences, economics, global villages, India, UC Irvine

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home