Like many in the UC faculty, I received my alarm e-mail notifying me that arch-conservative

UCLA Profs.com was offering to pay students up to $100 to tape lectures from the "radical professors" among my blue-and-gold colleagues at

UCLA. As of yesterday, the pay-for-replay offer has been withdrawn, apparently in the face of threatened litigation over intellectual property infringement, but the story has continued to garner an amazing amount of media attention, including an urgent bulletin on NPR during my morning commute.

I heartily agree with

Siva Vaidhyanathan of

Sivacracy.net that teaching is a public act and support the extended application of this principle into programs like the

Open Courseware Initiative at MIT. Fellow sivacracy blogger

Ann Bartow has also rightfully pointed out that using the intellectual property argument against the efforts of conservative alumni and mercenary students is a long-range tactical mistake, since what she considers to be corrupt means (privatizing part of the scholarly body of knowledge) contaminates potentially laudable ends (political resistance and the advocacy of unpopular opinions). But, as sage as I think the sivacracy bloggers tend to be, I still think they might be overlooking a major aspect of the case.

In my mind, this is not a story about a vast political conspiracy threatening academia (or even just

Lernfreiheit vs.

Lehrerfreiheit) as much as a story about

media literacy and one in which U.C. faculty members don't come off particularly well. This narrative contains two major elements:

1) UNDERSTATING THE CONVENTIONAL CHARACTER OF A GENRE'S STOCK FEATURES

New genres and mixed genres on the web sow confusion. The UCLA Profs web page is now being treated as a serious alumni site, but it actually belongs to a popular class of websites that primarily serves undergraduates, with the most successful example being

ratemyprofessors.com. The design sensibility of the 1-5 "power fist" designation of UCLA Profs differs from the visual branding of other ratings sites, which use graphic icons, but the layout, the length of each entry, and the general tone of the reviews is comparable. Based on my own frequent surveys, I can assert that many similar professor-rating sites also share the same basic flaw of disinhibiting users who submit a disproportionate number of unfair criticisms of faculty who are feminist, lesbian, or people of color.

Of course, when it comes to evaluations, there has to be a better way. My undergraduate alma mater always made its

official evaluations available to students, which I think considerably lessens the attractions of anecdotal online reviews. I'll even acknowledge that some studies show that

official evaluations can be skewed, but I would still say that making a teaching record accessible fosters better pedagogy and more inclusive discourse in academic communities.

I, personally, am morbidly fascinated with the viciousness of the virtual crowd at ratemyprofessors.com. I will even confess to once visiting

the page by students rating Stanley Fish, after reading a particularly improbable

New York Times editorial, "

Devoid of Content," in which Fish advocates having students

make up a language in their college composition classes rather than actually develop some mastery of the language they are currently assigned.

And, speaking of improbable claims, this brings me to my second criticism of the general faculty response to the UCLA case . . .

2) OVERSTATING THE AUTHORITY OF A QUESTIONABLE SOURCE

Why is it that teachers spend so much time talking about students' lack of Internet skepticism and spend so little time examining their own? It's true that in my experience an entire college classroom once believed that a stealth marketing website promoting the movie

X-men was a credible source for researching human cloning. But it's also true that my fellow instructors have fallen for self-righteous campaigns against

Bonsai Kitten and diatribes against the

Unreal Tournament Bible Based Maps and other parodic bandwagons for the credulous.

Despite the organization's official sounding name, the

Bruin Alumni Association, I can't find evidence that anyone other than twenty-four-year-old Bruin Alumni Association President Andrew Jones is associated with this august body (at least until he received all this media attention). As of yesterday, there didn't even seem to be a Vice President to be found. I couldn't locate content generated by the grown-up members of the "

advisory board," some of whom had resigned in protest according to NPR. If anyone thinks this site was engineered by political insiders or powerful robber barons, a few clicks to Andrew's earnest face or his terribly written blog would disabuse them of this notion. To see what I mean by the kind of smog check that Jones could never pass, see librarian Susan Beck's now classic "

Evaluation Criteria for 'The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.'"

I'm still amazed that this epistolary volley discharged like the newest computer virus hysteria and ricocheted through hundreds of academic departments, and no one paused before pumping the forward button. Reuters and CNN fastened upon the website thanks to multiple e-mails stacked up in faculty inboxes and not to the efforts of Mr. Jones himself. I might even guess that the site would never have been found by the public at large if it weren't for one of the named professors googling him or herself one night.

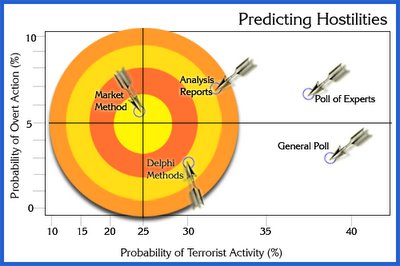

Ignored, the story would have gone nowhere. Validated, it may become an issue for a larger and more critical constituency: the taxpayers who support the U.C. system. Particularly at a time when digital rhetoric and the distributed discourses of the public sphere are being co-opted by vested interests in

Public Diplomacy,

Social Marketing, and

Risk Communication, it is important to avoid crying wolf.

(To read an opposing viewpoint, see the impassioned missive posted on

Inside Higher Ed that directly addresses Andrew Jones and the Bruin "group" and takes serious issue with their claims. This open letter by fellow Core Course instructor Brian Thill, "

An Idea Too Dangerous to Ignore," is full of excellent arguments and reflections, even if I might argue that it is better suited to a Governor or a Chancellor than to a recently graduated Internet crank.)

Labels: close reading, higher education, hoaxes, teaching, UCLA