The reaction to

Siva Vaidhyanathan's alarm-ringing about

Google Book Search has grown particularly acrimonious in recent weeks. In

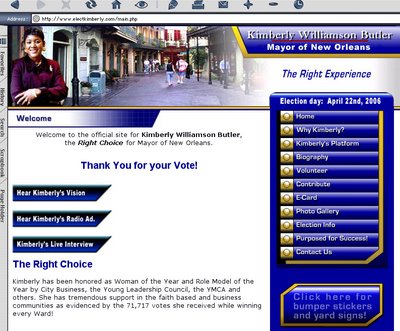

Sivacracy.net, Vaidhyanathan has reprinted some of the juicier diatribes by Google advocates in the library community, including

Walt Crawford's comparison of the politically progressive media scholar and cyber-activist to right-wing environmental figurehead

Gale Norton. (See above.)

Does this mean that Vaidhyanathan's plan for creating an academic discipline around what he has called "

Critical Information Studies" (or "CIS") in a recent manifesto is unraveling? This intellectual enterprise will certainly require an ambitious programme of collaboration, as Vaidhyanathan envisions it.

CIS captures the variety of approaches and bodies of knowledge needed to make sense of important phenomena such as copyright policy, electronic voting, encryption, the state of libraries, the preservation of ancient cultural traditions, and markets for cultural production. It necessarily stretches to a wide array of scholarly subjects, employs multiple complementary methodologies, and influences conversations far beyond the gates of the university. Economists, sociologists, linguists, anthropologists, ethnomusicologists, communication scholars, lawyers, computer scientists, philosophers, and librarians have all contributed to this field, and thus it can serve as a model for how engaged, relevant scholarship might be carried out. It's obvious that corporate interests shouldn't be enabled in perpetuating academic factions, but it's less obvious how cross-professional communities can be maintained. Of course, librarians are a critical part of the field that is being outlined. Some might gripe that Vaidhyanathan puts them last on his list, but his work on copywrongs and public culture places him solidly on the side of the action agenda of the ALA. And I'm assuming that "rhetoricians" belong with "communication scholars," so I don't plan on being piqued about any perceived oversight on his part.

These fractures aren't surprising. My distant cousin

Clark Kerr once said the university really was a "multiversity" with many competing stakeholders. Certainly, the traditional divide between teaching and research is still policed, and further schisms are generated by the interventions of graduate students, undergraduates, administrators, alumni, community activists, elected officials, life-long learners, consultants from the private sector, and -- of course -- librarians.

James Elmborg has argued that librarians and compositionists are natural allies, because library instruction and writing instruction face similar obstacles to finding an appropriate place in the university curriculum. Both programs are often seen as either offering

remediation (teaching skills that students should know but do not) or

inoculation (teaching students something once, so they will learn and know it always) or both, rather than as teaching a stand-alone curriculum that also has the potential to

enrich and

enhance student learning outcomes.

I suppose Elmborg's thesis could be recast as a nice way of saying that compositionists and librarians are both part of the permanent academic underclass of elite institutions. In other words, there is a caste system in which "knowledge workers" are superior to "information workers," as John Seely Brown says in

The Social Life of Information. Or, to use Mary Douglas's categories of analysis from

Purity and Danger, these professionals are polluted by duties that bring them in contact with different forms of undergraduate illiteracy, so that their expertise makes them into untouchables.

These divisions are further exacerbated when new technologies and media are introduced. According to

a CCC study, deans and department chairs from humanities departments find work with digital media to be of questionable value for tenure and promotion in the academy. Those who participate in this real labor in virtual environments are confused with "tech people" or disposable "support staff."

This academic politics of exclusion and consolidation is not just a problem in departments centered around literature. Computer scientists also don't want to be affiliated with impure humanistic fields. Perhaps the classic piece of rhetoric in this area is E. W. Dijkstra's "

On the cruelty of really teaching computer science," in which he recognizes the radical paradigm shift created by the discipline of computer science, but uses this disjunction as an excuse for retreating into pure mathematics and eschewing all forms of HCI.

For lack of a better word, I've called this principle of inevitable backlash against interactive, networked technology

Virtualpolitik or the

Realpolitik of virtual institutions. Quite understandably, CIS triggers these rivalries. Such scholarship involves addressing questions of ideology and interrogating lived discursive practice and thus "interferes" with established cultural norms of professional association. As Vaidhyanathan writes,

CIS interrogates the structures, functions, habits, norms, and practices that guide global flows of information and cultural elements. Instead of being concerned merely with one's right to speak (or sing or publish), CIS asks questions about access, costs, and chilling effects on, within, and among audiences, citizens, emerging cultural creators, indigenous cultural groups, teachers, and students. Central to these issues is the idea of "semiotic democracy," or the ability of citizens to employ the signs and symbols ubiquitous in their environments in manners that they determine.

I should also probably add a disclaimer about possible bias. Readers of this blog know

my opinions about Google Book Search and the fact that I agree with Vaidhyanathan, but others may not. My point of view on this subject has a history that goes back to my work on digital libraries that appeared in the form of a 2004 article on "Reading Room(s): Building a National Archive in Virtual Spaces and Physical Places" in

Literary and Linguistic Computing from Oxford University Press. I would hope that having such opinions wouldn't distance me from my friends and colleagues who are librarians. For example, I've given papers with U.C. Irvine's

Catherine Palmer to receptive audiences at conferences in both disciplines.

I don't see why defending the public character of digital archival projects should interfere with these productive collaborations. And I certainly don't think Vaidhyanathan is crying wolf, particularly about the importance of

open document formats and open metadata standards.

Finally, thanks to

Mel Horan, creator of anti-consumerist webtoon

Garbage Island for the Vaidhyanathan/Norton image. For more on this kind of image and the rhetoric of aesthetic juxtaposition, see "

The Art of Argument" on this blog.

Labels: composition, digital archives, Google, search engines