I won’t be cramming onto a plane this weekend, spending a month’s salary on a plush hotel suite, haggling for tickets, or planning my assault on the Washington mall with other jostling out-of towners. It’s not that I’m not excited about seeing Barack Obama be sworn in as 44th President of the United States, but for me there are a thousand practical reasons for staying in California on January 20th. So I will watch the event on television, like most Americans.

I will also be watching it on my computer screen, thanks to the mobile devices of friends, acquaintances, and even strangers who will post their impressions of the Obama inauguration on Facebook, Flickr, YouTube, and Twitter. With unprecedented access to tools for creating and disseminating digital media, the record of this inaugural ceremony could show the richness of American pluralism, populism, and democratic inclusiveness with many individual perspectives.

However, before this electronic testimony is collected, we have an opportunity for critical reflection about how it will be archived for future generations. I talked to three Obama supporters and Facebook “friends” planning to join the inaugural festivities: a black woman, a white mid-career father, and a young Chilean immigrant. Despite different viewpoints, what they said resonated with my own concerns about commercial sites that are ill-equipped to be public archives.

My friend Alison, a television writer going to at least one A-list reception, may post an album of photos from the inauguration to Facebook, but she’s wary of “planning to subject everyone I know to the equivalent of a slideshow.” As an African-American, she feels the event’s significance personally, but she wants to opt out of “an international status check” that reduces the start of a new political and cultural era to “standing next to so-and-so.”

“I want to experience the experience,” she asserts. “To constantly document the moment is to take yourself out of it. A ‘community’ that incessantly asks for feedback is isolating. You lose the ability to process your own emotions and categorize your own feelings.”

In contrast,

Michael Powers produces

one of the Twitter feeds I will follow inauguration day. When listing reasons he is willing to cope with logistics that at one time included a 4 A.M. Metro ride and figuring out “how you change a two-year-old standing up in 30-degree weather,” he begins with the easiest explanation: “We’re insane.” He also describes his entire family working on the campaign in a “definite minority” of liberals in Indiana, Pennsylvania. “We have a strong sense of community around the campaign, and going down together is a way of keeping that sense of community going.” He wanted his kids “to bear witness to how local actions can have national results,” but has decided to go solo, because of the crowd, and will also be sharing the event with them through mobile devices for ubiquitous computing.

Powers is well aware that unlike scrapbooks or photo albums, which exist as physical objects, the digital record transmitted from his phone to Facebook and Twitter will be stored on remote servers in what information technology specialists like himself call “the cloud.” That’s why he’s on the Twitter public timeline, despite bandwidth issues, since text is “theoretically easiest to archive.” As he observes, "ASCI is forever." He’d upload his inauguration photos to Flickr, but recently he’s been mysteriously locked out of his account.

I’ve never met twenty-five-year-old blogger

Pablo Manriquez, but I’ll be following his

Twitter feed as well. Although he hadn’t worked out exact plans for getting from St. Louis to Washington D.C. at the time of our conversation and was grappling with the complexities described in

Documenting the 2009 Presidential Inauguration, this aspiring photojournalist and contributor to

Now Public is expecting to document the event with pictures on Facebook, Flickr, and Google’s Picasa. Like Powers, he has had problems with having accounts suspended, twice on Facebook alone.

As a former history student, Manriquez worries how inauguration material will be archived for posterity, even though technologies can stamp images with exact times and locations pinpointed to within a foot. “The cloud’s a great thing, but unlabeled data isn’t.” He compares information haphazardly uploaded to the Internet without explanation to materials in London’s

Foundling Museum, which warehouses the 18th-century artifacts mothers left with abandoned children, such as spoons or lockets. “In the digital sense,” says Manriquez, “there will be a lot of lockets” from the inauguration.

According to Kris Carpenter, volunteers from the

Internet Archive intend to be dispersed among the crowd on Tuesday, armed with laptops and “every adaptor they can think of” to collect data from cell phones and digital cameras from attendees and provide cataloging information or “metadata” to identify sources on the spot. The problem for archivists like Carpenter is that commercial sites like Facebook aren’t designed to commemorate national oratory or ritual observance; they are designed to generate advertising revenue and marketing data by capitalizing on the digital collections of others, which they take little responsibility for maintaining.

Pundits in the mainstream media have a tendency to chastise Internet users for making their private lives public and for putting the most intimate or mundane details of their personal experiences into digital files for all to gawk at online. As a scholar of rhetoric, my fear is that these practices won’t be public

enough now that so many people rely on corporate cloud computing to store and share photos, videos, and journal entries.

Historians will want to mine this treasure trove of historical data, but the privacy architectures of “friends-only” websites, the rules in user agreements, and technologies that prevent copying may thwart collecting this material, and – as Powers and Manriquez have discovered – accounts can be suspended or deleted with little cause by dot-com corporations that may not last into the next century.

Dan Cohen, head of the

Center for History and New Media at George Mason University agrees there are many problems with “online memory-making with decentralized user contributions” dependent on organizations “not in the forever business.” Rather than post to Facebook, Cohen encourages attendees to upload content to

An American Moment: Your Story at Change.gov. Yet Cohen also praises the resources of commercial sites with public viewing privileges and fewer copyright restrictions. “After the 2005 London bombings, there were more photographs on Flickr than Scotland Yard could ever have gathered.”

Rather than try to keep up with all the digital ephemera on the web, the

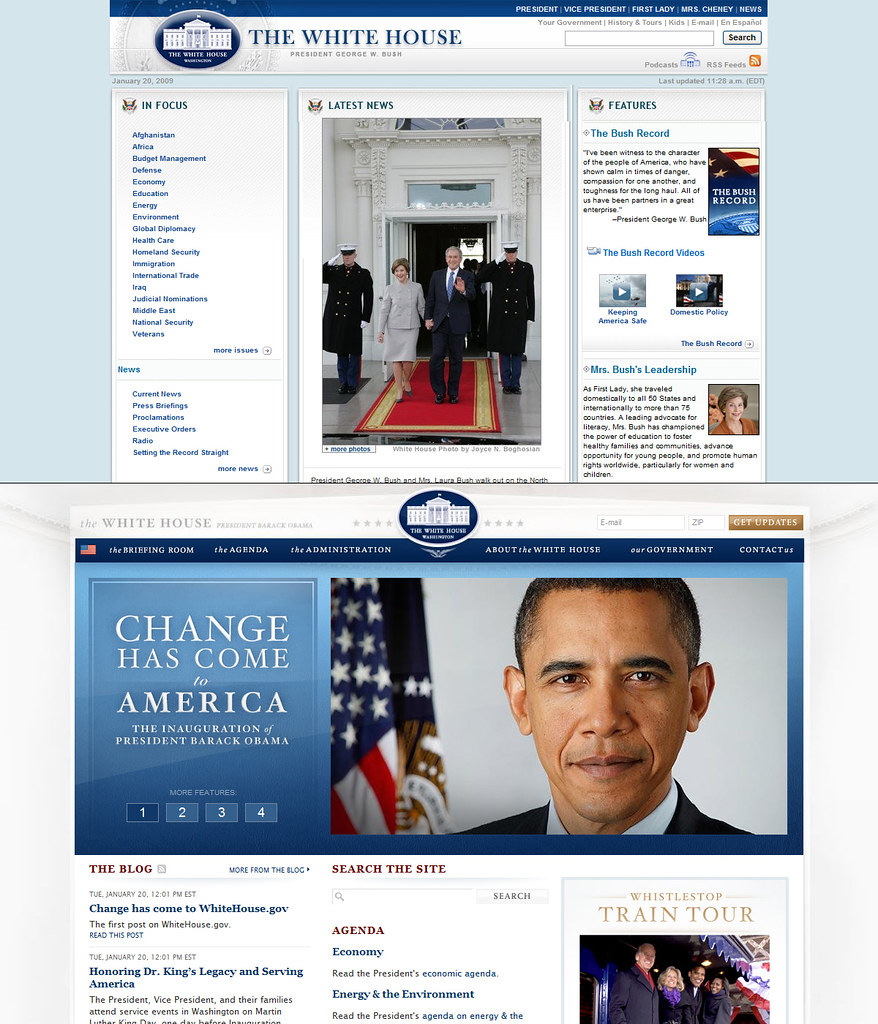

Library of Congress is concentrating on official websites like the Obama-Biden transition team’s

Change.gov. However, as the Library's Abbie Grotke explains, even government agencies are putting large amounts of historically significant web content onto commercial third-party sites like Flickr, YouTube, and Twitter.

Jennifer Gavin at the LOC points out that citizens can also contribute to the

Inaguration 2009 Sermons and Orations project. Rather than posting to private walls and putting more data into the cloud, inauguration attendees could upload material to government sites like

Change.gov and nonprofit sites like the

Internet Archive, so we can all feel like part of the crowd in the future.

Labels: digital archives, White House

But when is the writing for the web going to get any better? When will there be any actual information in the posts that citizens might choose to forward to each other? When, at the very least, will you start hyperlinking more regularly, perhaps to other diplomatic blogs from other countries?

But when is the writing for the web going to get any better? When will there be any actual information in the posts that citizens might choose to forward to each other? When, at the very least, will you start hyperlinking more regularly, perhaps to other diplomatic blogs from other countries?