Today I voted well in advance of election day, thanks to a touch-screen voting site. I even have my "I Voted Touchscreen" sticker to prove it. Based on my experiences, I would add a few things to

this excellent list written by Siva Vaidhyanathan:

1) The machines offer less privacy to voters not more.

2) The machines slow down the voting process and tax the attention of poll workers rather than improve efficiency.

3) The touch screen interface is surprisingly poorly designed for the visual presentation of information. This is an obvious missed opportunity, given how easily color, dynamic text, and the intuitive movement of icons could have been cheaply used.

4) The machines break down and thus compromise the entire process.

5) The machine's instructions are designed to be literal-minded and serve to match the computer's standardized algorithm not the intention of the ballot makers. For example, the text on the touch screen was significantly different from the text on a printed ballot when it came to more complicated "no more than X" elections.

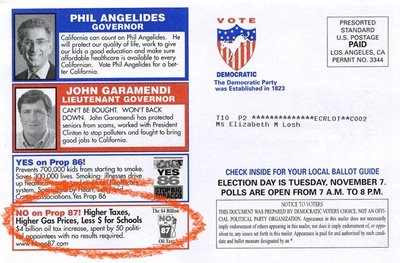

In California, there has been considerable publicity about

Sequoia Voting Systems, which makes the machines used in sixteen counties in the state, including nearby Riverside and San Bernadino districts. At issue are possible corporate ties to Venezuela and the government of anti-US firebrand Hugo Chavez. However, the Sequoia company says it welcomes an investigation, according to a story in

The Los Angeles Times, "

Vote Machine Maker Asks U.S. to Probe Alleged Ties."

Like the rest of the early voters in Los Angeles county, I had to trust my vote to a shiny

Diebold voting machine, which has perhaps an even more suspect history of political interest. In today's

LA Times, an editorial on how "

E-voting may be scarier than hanging chads" points out how vulnerable the machine's security systems are to tampering. Luckily, the ones in LA County have a paper receipt that the voter can review under a plastic shield.

At my e-voting place, people who had their sample ballots with pre-printed addresses didn't have to prove their identities. I didn't have mine, so I filled out and signed a blue form, so poll workers could pull up my voter registration information on their laptops. (I don't know what they do with provisional voters, whose ballots are usually kept apart until they have been verified.) I was issued a white "voter access card," which had a gold computer chip implanted in its surface. While we waited, prospective voters sat in rows of folding seats and periodically played what the poll workers called "musical chairs" each time a booth was free.

The privacy of the machines was terrible, particularly for senior citizens who used the "high contrast" or "large text" options. It was easy to see exactly for whom particular people were voting; no craning of necks or theatrical snooping was necessary. I had to control the urge to say things like "I liked him better in the first

Terminator" or "Good to see that the oil companies weren't wasting their money with those TV ads."

When I got up to my own machine, which had a large sticker warning about the penalties for tampering with it ($50,000 and four years in state prison), I was certainly underwhelmed by the quality of its information design. Even though the device offered ballots in eight languages, there were many obvious ways to improve the user-interface design that had been overlooked.

For starters, the instructions weren't well written or logically sequenced. Of course, I am someone who refused to re-elect a judge on the grounds of the multiple split infinitives in her opening election statement, so perhaps I am excessively picky about language. But the instructions also didn't take advantage of the visual nature of the display to show sample screenshots or even the most relevant buttons to push, which anyone new to the system would have appreciated.

When I started going through the actual twenty-one page ballot, I was even more surprised to see that color wasn't used to provide additional differentiation, at the very least for candidates from different political parties. A relatively monochromatic solid yellow and solid white ballot may look more dignified, but it doesn't do much to make sure that people are touching the box on the same line as their candidates. Furthermore, the procedure for write-in candidates, which involved bringing up a virtual keyboard, was unwieldy. Then, when the time came to review the ballot, there was an awkward scroller and results in clumsily staggered columns so it was hard to keep track of contests already reviewed without skipping.

The architects of this electronic ballot would surely get a low grade in any college web design course for their work.

Certainly, the new machines weren't speeding up the voting process any either. Impatient voters were stacking up behind each other, as people puzzled over their cryptic screens. When an additional relief worker appeared mid-day, the other poll workers greeted her with joy. As I was voting, I heard poll workers discussing the machine that was no longer operational, as one that had "expired" or "passed away." Just as they said this, a repairman came to revive the machine that had met its demise. But I noticed that they didn't check the ID around his neck before unlocking the vault to the mechanism. I hate to sound paranoid, but it's important to remember that a lot of what we think of as "computer fraud" or "data theft" is actually perpetrated by traditional analog imposters or low-tech dumpster divers. Yet, to give the overworked inspector his due, he did ask the fellow's name before he left the polling place.

Strangely, when the repairman started up the machine, he didn't see any problems at all, although the poll workers had been complaining of "bad memory" error messages. A defective sensor was blamed for the problem, and the machine was put back into service. During the repairman's visit, the poll inspector complained that when he booted up all the machines that morning, the screens all said that the devices were out of paper, even though they weren't.

Finally, this may sound like a relatively minor point, but I was bothered by what was lost in translation from the printed ballot to shorter text on the screen. My printed ballot had several municipal contests in which the voter was instructed to "vote for no more than four" or "vote for no more than three" candidates. On the screen, however, it simply said "vote for four" or "vote for three." Then, when I was reviewing my vote, these sections turned pink, as though I had undervoted in error. Of course, I

meant to to vote this way; it's a legitimate and commonly pursued voting strategy in local elections with small vote totals that can be easily swayed. Official voter guides often advise particular constituencies to vote for fewer candidates than the total number of slots. But a less knowledgeable voter might assume that such a vote didn't count and would be considered a mistake.

It shouldn't count as electioneering that one of the poll workers told me that if I didn't like Diebold machines I could vote the people who liked them out of office.

Labels: elections